Virtual displacement

A virtual displacement  "is an assumed infinitesimal change of system coordinates occurring while time is held constant. It is called virtual rather than real since no actual displacement can take place without the passage of time."[1]:263

"is an assumed infinitesimal change of system coordinates occurring while time is held constant. It is called virtual rather than real since no actual displacement can take place without the passage of time."[1]:263

In modern terminology virtual displacement is a tangent vector to the manifold representing the constraints at a fixed time. Unlike regular displacement which arises from differentiating with respect to time parameter  along the path of the motion (thus pointing in the direction of the motion), virtual displacement arises from differentiating with respect to the parameter

along the path of the motion (thus pointing in the direction of the motion), virtual displacement arises from differentiating with respect to the parameter  enumerating paths of the motion variated in a manner consistent with the constraints (thus pointing at a fixed time in the direction tangent to the constraining manifold). The symbol

enumerating paths of the motion variated in a manner consistent with the constraints (thus pointing at a fixed time in the direction tangent to the constraining manifold). The symbol  is traditionally used to denote the corresponding derivative

is traditionally used to denote the corresponding derivative  .

.

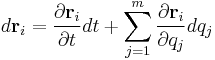

The total differential of any set of system position vectors,  , that are functions of other variables,

, that are functions of other variables,  , and time,

, and time,  may be expressed as follows:[1]:264

may be expressed as follows:[1]:264

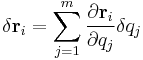

If, instead, we want the virtual displacement (virtual differential displacement), then[1]:265

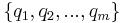

This equation is used in Lagrangian mechanics to relate generalized coordinates,  , to virtual work,

, to virtual work,  , and generalized forces,

, and generalized forces,  .

.

In analytical mechanics the concept of a virtual displacement, related to the concept of virtual work, is meaningful only when discussing a physical system subject to constraints on its motion. A special case of an infinitesimal displacement (usually notated  ), a virtual displacement (notated

), a virtual displacement (notated  ) refers to an infinitesimal change in the position coordinates of a system such that the constraints remain satisfied.

) refers to an infinitesimal change in the position coordinates of a system such that the constraints remain satisfied.

For example, if a bead is constrained to move on a hoop, its position may be represented by the position coordinate  , which gives the angle at which the bead is situated. Say that the bead is at the top. Moving the bead straight upwards from its height

, which gives the angle at which the bead is situated. Say that the bead is at the top. Moving the bead straight upwards from its height  to a height

to a height  would represent one possible infinitesimal displacement, but would violate the constraint. The only possible virtual displacement would be a displacement from the bead's position,

would represent one possible infinitesimal displacement, but would violate the constraint. The only possible virtual displacement would be a displacement from the bead's position,  to a new position

to a new position  (where

(where  could be positive or negative).

could be positive or negative).

It is also worthwhile to note that virtual displacements are spatial displacements exclusively - time is fixed while they occur. When computing virtual differentials of quantities that are functions of space and time coordinates, no dependence on time is considered (formally equivalent to saying  ).

).